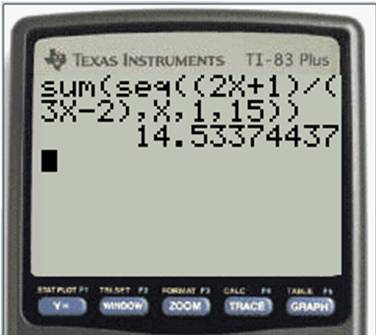

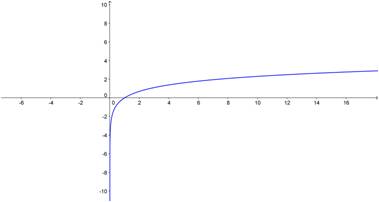

Can you find the sum of the following series?

This is neither an arithmetic nor a geometric series, so you don’t have a formula for it. This would be a tedious problem to do by hand. Fortunately, your graphing calculator can do these problems quickly and efficiently.

There are two functions you need to use on your calculator. The seq( command creates a sequence of terms based on a rule that you give. The sum( command adds together the terms in a sequence. Both functions are found on the LIST menu on your calculator. The seq( command is on the OPS submenu and the sum( command is on the MATH submenu.

To sum a series, you combine the two commands. If you have the new operating system on your calculator, it will prompt you for the entries when you select the seq( command. If you have the old operating system, you need to know the syntax for the command. The syntax for the series above is:

sum(seq((2x + 1)/(3x – 2),x,1,15))

Note that the seq( command has four parameters in the parentheses. From left to right, these are 1) the rule for the nth term of the sequence; 2) the variable name; 3) the first value of the variable; and 4) the final value of the variable. Now all you need to do is type this in to your calculator and let it do the crunching: